Chef Greg Gable, whose résumé includes high-profile positions at The Restaurant at Doneckers and the heralded Le Bec-Fin in Philadelphia, now shares his wisdom with home cooks and professional chefs through Savencia Cheese USA, where he is the corporate chef.

As with many successful chefs, Greg Gable’s prolific career grew out of humble beginnings. His interest in the workings of a professional kitchen started early, when he was still a student at Garden Spot High School in New Holland. Greg got his start at the Colonial Motor Lodge near the Pennsylvania Turnpike interchange in Denver. “That was my first real cooking experience,” he recounts. “I started as a bus kid at the Colonial and soon figured out that was not for me.” Advancing to the role of dishwasher, he then worked his way to cooking breakfast and lunch. “Cooking breakfast was awesome,” he says. “The fast pace, it’s crazy. Flipping eggs. That’s where I learned to cook for the first time.”

The experience sparked a passion in Greg that led to the Culinary Institute of America (CIA). After graduating in 1984 he began working for Bill Donecker at The Restaurant at Doneckers in Ephrata. His big move came in 1987, when he began a 14-year run at the esteemed Le Bec-Fin in Philadelphia, under chef/owner Georges Perrier, who had emigrated to the United States in 1967 and opened Le Bec-Fin in 1970. Regarded as one of the top French restaurants in the United States and Philadelphia’s finest restaurant for over 40 years (it closed in 2013), Le Bec-Fin won 10 James Beard Foundation Awards between 1992 and 2002, as well as countless other honors.

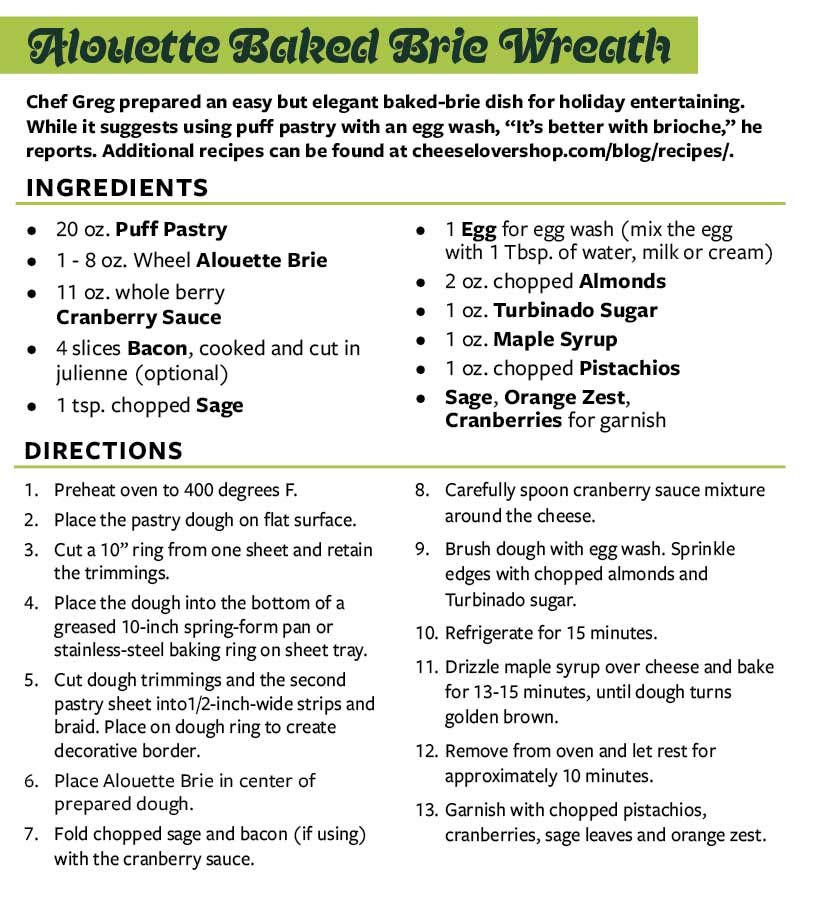

The assembled ingredients include vibrant garnishes of purple and common sage, orange zest, chopped almonds and Julienned bacon.

Greg returned to Doneckers as executive chef in 2001, working with his wife, Heidi, a sommelier. “She’s the wine expert. It was fun working with her,” he says of the almost four-and-a-half years they collaborated on tasting menus and wine pairings.

Cheese R&D

Greg became Savencia Cheese USA’s corporate chef in 2006. (Heidi went in another direction and became Kitchen Kettle Village’s human resources coordinator in 2012.) Perhaps best known locally as the maker of the Alouette cheese line, the Savencia Groupe is ranked as the fifth-largest manufacturer of cheese (many of them world-class) in the world. According to its website, Savencia products are sold in 120 countries.

Alouette’s Double Cream Brie, a soft-ripened cheese, can be aged in the refrigerator for added richness in texture and flavor.

Despite having a global reach, the company thinks on a local level and touts its mission as “Leading the way to better food.” Savencia also champions the premise of positivity as it relates to leading a healthy and responsible lifestyle without having to give up the pleasures of life from a dietary perspective.

“Our owner, Alex Bongrain, worked here in the 1970s, when we started making cream cheese,” Greg recounts. “There’s a story [that] Savencia was started by the Bongrain family after World War II. Like everyone in France, they were making Brie-style, soft-ripened cheeses. Jean-Noël Bongrain asked what he could do to make his cheese stand out. So, he made an oval-shaped soft cheese, Caprice de’Dieux. He put it in this blue packaging 65 years ago; this was revolutionary back then. That’s what started our company. You can say ‘Caprice de’Dieux’ to anyone in France and they will know exactly the cheese you are talking about.”

Home base for Greg is the Steve Schalow R&D Center on Jackson Street in New Holland. Named in remembrance of Greg’s friend and former boss, Steve worked as a microbiologist studying cheese cultures.

Here, on Jackson Street, Greg focuses on food testing, quality control and developing innovative product flavors. Since Savencia’s New Holland facility specializes in producing cream cheese, Greg often bakes cheesecakes for testing purposes. When he ventures to food shows across the globe, he assumes an educational role in displaying cheeses and preparing recipes. “I’ve been to China, Brazil, Vietnam, Germany, France, and all over the United States,” he shares.

Maple syrup is drizzled over the brie before baking, ensuring sweet and savory flavors and creamy and chewy textures.

A recent excursion took Greg to Washington, D.C., where he represented Savencia at a dinner that is held for the Master Chefs of France (Maîtres Cuisiniers de France) every September. It’s hosted by the French Embassy at the Ritz Carlton Hotel.

Savencia sponsored the cheese course for this year’s dinner. “My boss at Le Bec-Fin, Georges Perrier, was a Master Chef. It’s an honorary [title] in the culinary world for having an influence on cuisine,” he explains. Savencia’s world-class cheese platter included Esquirrou, Epoisse and Rogue River blue cheeses, each of which has claimed a world championship.

The Flagship

Made in New Holland, “Alouette Garlic and Herb is our flagship,” says Greg. A soft and spreadable cheese, he points out that “cream cheese is considered a fresh cheese. It’s stable over its shelf life, which is typically 90-120 days, depending on the packaging. We try to keep as much oxygen away from it as possible and use full-fat milk. Cream cheese is full-fat milk, heavy cream, cultures, salt and gum. We have a method to add fresh herbs to it without cooking it. That adds quality.”

Greg adds that he and the staff are always asking themselves how they can improve it without deviating from the core of the product. (It seems a chef is always a chef!) “As a chef, you are trained in a classic sense. That gives you the basics,” Greg relates. Through research, he delves into new ingredients and trends. “Knowing what you know, what flavors work together, through trial and error, I get to make wacky Alouette flavors.”

Determining if a new cheese will make the cut takes time. “In a restaurant, you buy an ingredient and make something out of it. It’s a pretty quick cycle,” he says. He uses his restaurant experience to explain the nuances of determining if something “spoke” to guests. “We used to hold empty plates up at the restaurant and go, ‘You don’t have to wash that one, they liked what they were eating.’ I can still see [chef] Georges doing that to this day. It became a joke after a while, but it’s true. If nothing is left on the plate, either you didn’t give them enough or they really liked it,” he elaborates.

At companies like Savencia it’s a different ballgame, as the chain of events to manufacture a product is so much longer and more detailed. “Here, we have to think about packaging. Shelf life. How is the end user going to use it? How will it get there?” Greg explains.

The packaging is important since it has a surprising impact on flavor. “Dairy is very susceptible to light oxidation,” Greg shares. “It happens within 24 hours.” When oxidized, an aroma and taste develop, which he describes as “wet cardboard.” Subsequently, Alouette cheese containers are designed with a light barrier.

Alouette Baked Brie Wreath, perfect for dipping, can be prepared quickly in a small convection toaster oven using puff pastry, a wheel of soft-ripened cheese, fresh herbs, fruit and other items. An egg-wash brushed on the crust before baking enhances the color and texture of the baked dough. See recipe below.

The Jackson Street facility serves as the pilot plant for products. Here, personnel mimic the process that the factory will use when the manufacturing process begins. “Then it will get to the plant, we’ll start producing it, scale up, and we’ll conduct shelf-life testing, validating the product,” Greg explains. “Shelf life isn’t something we determine, the customer we sell to determines that date. We have to validate and test [the product] to make sure it’s food safe and the quality we want.”

Soft Ripened

To be clear, in order to call a soft-ripened cheese “Brie,” it should technically be made in the Brie region of north-central France. The term has become interchangeable with soft-ripened cheese, akin to calling sparkling wine “Champagne.”

“All cheese looks like cottage cheese at some point,” says Greg. “Big curd, small curd, tiny curd, then it knits together and becomes the cheese. As they dry out and the whey drains, they become more yellow, but in the beginning, they’re very pale.”

“Cheesemaking is how you manipulate removing the whey from the fat, protein and solids,” he notes. “The smaller the curd, the drier the cheese. For soft-ripened cheese, you want large curds; you want to keep and protect the moisture. For hard cheeses, like Parmesan, you want to get more whey out of the curd.”

“Making wine is very similar to cheesemaking,” he professes. “Press the grapes, keep the juice. He goes on to say that the French term, “terroir,” which relates to how the environment in which the grapes are grown affects the taste of wine, also applies to cheese. “Whatever that mammal is eating will come through in the milk,” he says.

“Soft-ripened cheeses need oxygen, they are constantly evolving and aging,” Greg points out. A test you can conduct proves the point. Cut a wheel of soft-ripened cheese in half, eat one half and put the other half (loosely wrapped) back in the fridge. Mold will start to grow around the side, providing proof that the cheese is constantly evolving. Greg assures it’s still safe to eat. “We introduce the mold, just like a bleu cheese that introduces the bleu [mold] from the environment.”

“We make a single cream Brie with less fat for baking,” Greg describes. “It’s more stable, 50% fat from dry matter. Double cream is 65% fat, and triple cream is 75%. The lower the fat, the less oiling off. Double cream is typically the Brie you’re going to get.”

You’ve probably noticed that soft-ripened cheese becomes runny as it ages. “The fat’s breaking down, the protein is breaking down from the cultures you add upfront before aging, just like a wine,” he says of the processes that are known as lipolysis (think lipids or fat) and proteolysis (protein).

Pairing Wisdom With Cheese

Insulated from the restaurant industry, Greg’s career offers a noteworthy perspective for foodies and even chefs. “People don’t understand what [food] costs,” he says of the price tag for dining out these days. He also commiserates with restaurant owners who are constantly dealing with staffing issues. “God love these people who don’t have [enough] help,” he says.

He also empathizes with the servers and cooks who are being asked to go above and beyond. “They don’t get paid a lot of money,” he acknowledges, pointing out that such positions should pave the way to careers and therefore should not be dependent on tipping. “These servers are beat up. I see it all over the country,” he stresses. “I see it. I feel their pain everywhere I go.”

Greg adds that the current climate is one reason why he’s glad he no longer works in a restaurant. His advice to young cooks is to “expect to work hard. Learn to work efficiently. Learn your craft.” He also urges aspiring chefs to gain an appreciation for wholesome, quality ingredients that can impact the health factor of dishes.

Still, he has a place in his heart for the restaurant industry. “I miss the camaraderie, the action, the pace, the adrenaline rush,” he admits. However, he is quick to admit that the pluses don’t outweigh the negatives such as missing out on family time, having to forgo his daughter’s activities and simply having the luxury of doing nothing on a weekend. “I couldn’t have a better job,” he says of enjoying the best of both worlds in that he’s still involved in the food industry from a creative standpoint, but he has a better work/life balance that allows his creative “curds” to lead him in a variety of directions.

Where to Find It

CheeseLoverShop.com was launched in 2021 to allow consumers to literally taste the world of cheese. “Some of those cheeses we import from our sister companies, mostly from France,” Greg notes. “We also sell food-service whole wheels of these cheeses. All that comes through our distribution center in New Holland – they’re shipped over on containers from France.” Because some cheeses in France are often made to be eaten in 45 days, such products are delivered via air freight.

SHARE

PRINT