Sitting outside a beautiful, beachfront rental home on St. George Island, Florida, I never thought I would be reminded of Lancaster County. By now, however, I should know connections to Lancaster County are almost everywhere.

The Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead was saved from demolition by descendants of the first and only Stoltzfus to emigrate to America. Restoration continues and is being spearheaded by Elam Stoltzfus and a dedicated preservation committee.

On a particularly cool day I decided to forgo the beach and check out the one-light town on the barrier island separated from the mainland by Apalachicola Bay. I ended up at the Nature Center of the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve – a visitor’s center with winding nature paths, exhibits, an educational theatre and aquaria highlighting the regional watershed. Always ready to enjoy a good documentary, I sat down and watched Apalachicola River & Bay: A Connected Ecosystem. When the credits rolled, my jaw dropped when I saw: A Film by Elam Stoltzfus.

A name like Stoltzfus must surely be connected to Lancaster County. So, I decided to track him down.

The Filmmaker

It turned out Elam is a rather prolific documentary filmmaker. After finding an email address, I sent a hello detailing my experience in Florida. He responded with enthusiasm, excited to share his career and his latest project, which relates back to every (and I mean every) individual named Stoltzfus in Lancaster County. Intrigued, I headed to his home in Berks County to chat over coffee and fresh breakfast pastries.

Elam grew up near Morgantown, and his family was entangled in the “six things of ’66” event, which split the Amish Ordnung in Salisbury, Caernarvon and the Earl townships. When he was 10, his parents, along with approximately 30 other families, left the Old Order Amish church.

“That was a big deal, and at the same time a spiritual revival happened,” recalls Elam. His grandfather became the New Order bishop, fracturing the extended family. Many cousins on his father’s side became estranged and have remained so since the ’60s. After a couple of years, his parents joined a sister church in the Pequea area and moved to the Finger Lakes of New York in 1976. Crystal Valley Mennonite Church in Dundee, New York, is still operating today, and the family holds reunions there.

At 17, Elam left New York and hit the road with the Gospel Echoes Prison Ministry Band, touring full-time as a bass player. Over two years, he visited 36 states. While performing in Florida, he met Esther, his future wife. They married in 1985, after Elam earned a Bachelor of Arts in media and communication from Florida State University. And the bass was replaced with a camera.

“That was my jumping-off point for my career,” explains Elam. He did not know what kind of stories he would tell through film, but his love for the outdoors guided him. “When I picked up a camera it just worked. In film you have all the mediums – writing, photography, music – and it is very collaborative. I saw the impact and how film can emotionally move people. I thought, ‘This is how I can make a difference in the world.’”

Over his career, Elam has filmed and directed nine full-length films for public television and hundreds of smaller productions for TV and Florida visitors’ centers. His work ebbed and flowed, and Elam described it as a “feast and famine” profession. While VHS sales boosted his medium, DVDs sold less, and competing in the era of online streaming became challenging. After 35 years in filmmaking, he retired at age 62, against his wishes and desires.

Tragedy

“I was a passionate advocate for the Big River, as we called the Apalachicola River,” says Elam, who built a “dream house” with his wife in a small town near the Florida-Georgia state line. They raised children. He owned a horse. The couple planted a 20-acre forest of trees as commodities for their retirement. “The river was our playground. Holidays were celebrated with fireworks, fishing and water skiing. I spent many days and nights along the banks of the river exploring, filming and photographing the region.”

In mid-2018, a health diagnosis left Elam unable to continue as a film producer. Then, on October 10, 2018, Hurricane Michael made landfall with sustained winds of 160 mph. The Category 5 storm, the strongest on record to hit the Florida panhandle, maintained its destructive winds as it traveled north – as if it were following the river into Georgia. The Tallahassee Democrat newspaper described Blountstown as a “small town left as a wasteland.” “We lost everything,” says Elam. “It snapped our trees like they were toothpicks.”

He admits he was discouraged; however, Elam and Esther saw this as an opportunity to reconnect with their family and a fascinating heritage in Pennsylvania.

The Historians

“Every Stoltzfus you ever meet has roots to [the Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead]. Every single one. There’s only one Stoltzfus who ever came to America. And there are no Stoltzfuses currently in Germany that we can find,” says Elam. According to his calculations, about 80 percent of all Amish in Lancaster County have Stoltzfus roots. “I love telling this story,” he adds.

Elam leads me from the kitchen of his caretaker’s residence to the Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead, which he fondly calls the “old house.” Nicholas Stoltzfus, Elam’s ninth-great-grandfather, once lived there. As we enter, Elam recounts his 2018 trip to Germany, where he and fellow descendants of Nicholas dove into genealogical research. The group, which included German archive specialist Rosalind Beiler, collaborated with local historians to uncover the Stoltzfus legacy. There are stories of kings and queens, war and starvation, and forbidden love. Elam’s son, Nic, documented much of this history in his book, German Lutherans to Pennsylvania Amish, tracing the Stoltzfus name to 1624, when Paul Steltzenfuss married Margarethe Eberhart. Nic, who is deeply invested in preserving family history, has authored two books on the subject. “The surname ‘Stoltzfus’ is quite rare,” Nic writes. “If you meet a Stoltzfus in Germany today, their roots likely lead back to America.”

The name Stoltzfus of today can be translated to “proud foot,” but the first appearance is a bit less romanticized. Steltzenfuss translates to “stilt foot” and Elam’s research equates this to Paul’s vocation as a sheep farmer. Through the years the spelling has morphed, taking on meanings like “peg leg” or “one who limps.” Records from the 17th century are not too clear. What is without doubt is how four generations after Steltzenfuss, descendants Nicholas and Anna Stoltzfus boarded the Polly in 1744 and set sail for Philadelphia, becoming the first and only Stoltzfuses to immigrate to the “New World.” The family historians suppose the Stoltzfuses left Philadelphia by wagon and stayed near New Holland until purchasing the property where the Homestead stands. Inside the Homestead’s barn, a replica of the Polly’s interior offers visitors a glimpse into their journey.

The Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead

“My family up here had been asking me for a while, ‘Why don’t you come up here and tell the Stoltzfus story?” recalls Elam. “God has a way of redirecting you. After Hurricane Michael, moving up north looked much more appealing.”

The Homestead, a Colonial stone house built in the early 1700s, once housed Nicholas, Anna Elisabeth, and their four children. The family emigrated from Zweibrücken, Germany, and cultivated land along Tulpehocken Creek. Over the years, the property changed hands among several families. Today, it stands restored, hosting tours, educational programs and Amish history exhibits. It also serves as a gathering place for family reunions.

Descendants have donated historical items, as well. The homestead’s windows provide views of the picturesque grounds.

Unlocking the front door, Elam opens it wide. “Let’s get some air in here,” he says. The building has that Colonial smell of earth and old timber. Its functioning fireplace and period furnishings, donated by extended family or sourced at auction, make it feel like stepping into the past. “We don’t know exactly what the house looked like when Nicholas and Anna lived here because there has been work done on the house over the years.”

The homestead offers tours, as well as hosts educational programs and exhibits historical Amish items.

There are a few artifacts on display, including family holy books, records from the 1800s, and the original travel chest the Stoltzfuses brought to America. The chest is on loan from the Pequea Bruderschaft Library. But before the house came to this point it was set to be demolished. In 2000, PennDOT’s Park Road Corridor project looked to link a beltway around the city of Reading, and the old house was in the crosshairs. A grassroots effort of descendants successfully petitioned the state to reconsider the plans. However, after sitting vacant for many years the building was falling into decay and another inspired group of descendants, led by local historian Paul Kurtz, the Pequea Bruderschaft Library, and the Tri-County Historical Society, stepped up to form the Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead Preservation Committee, which worked with former Governor George Leader to attain preservation rights to the property.

Today, the Homestead remains a work in progress, striving to maintain its museum-quality status. A reconstructed barn, sourced from materials from a Lancaster County relative’s barn, adds to the site’s charm. Elam and Esther’s efforts as caretakers of the property (along with their son, Nic) have introduced revenue-generating opportunities, like a small one-bedroom apartment, which serves as a rental unit on Airbnb. The Stoltzfuses are working with a consultant to list the old house on the National Register of Historic Places, with plans to submit their application this year.

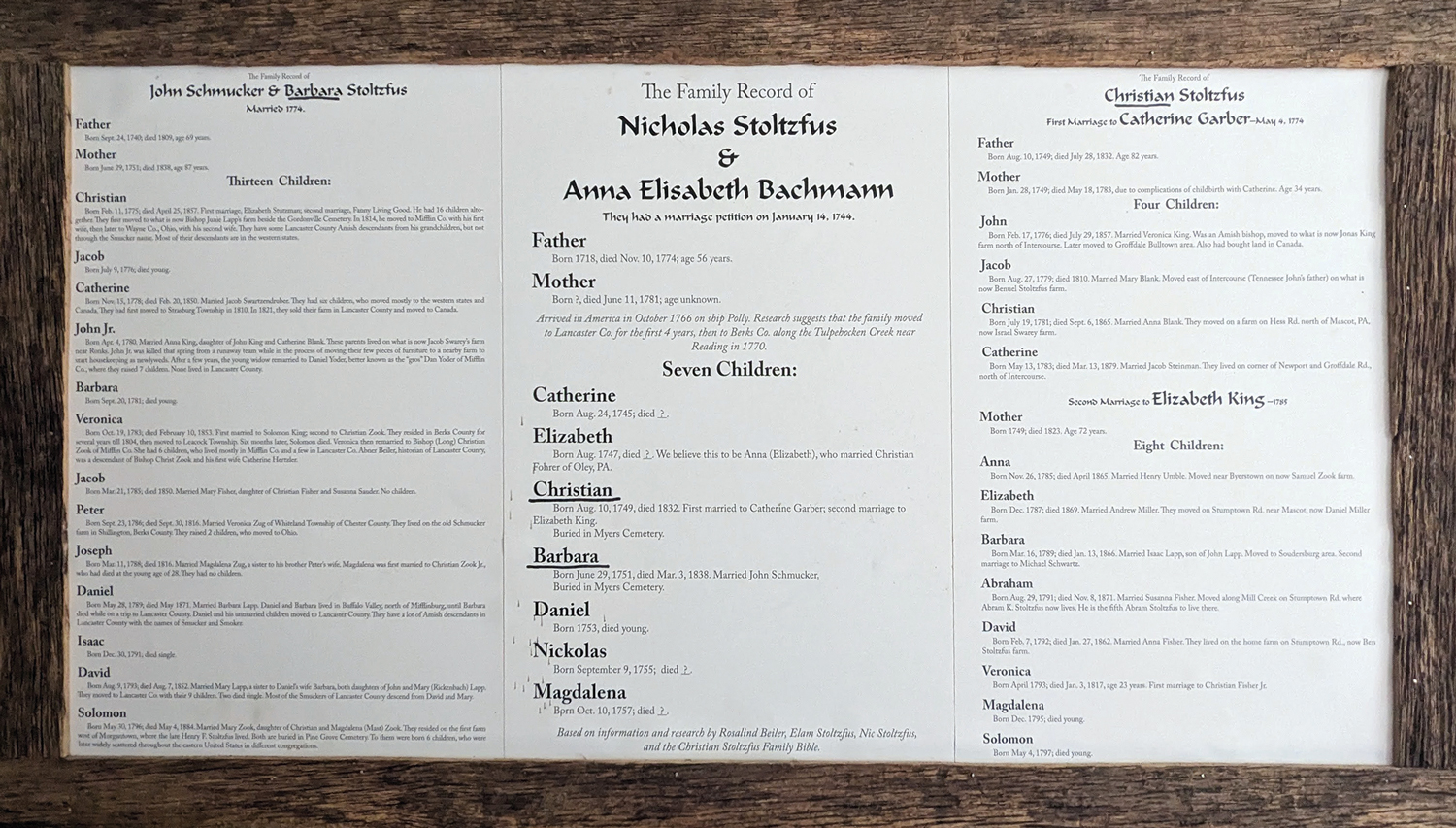

“We are also kicking off a new exhibit of a collection of 14 records of Amish families from the 1800s that have their roots (in) Berks County,” adds Elam. The exhibit will be open to the public every Friday and Saturday from 10 a.m.-4 p.m. from now through December.

Elam, members of his family, and German archive specialist, Rosalind Beiler, dug deep into historical documents to verify the lineage of the Stoltzfus name.

By reconnecting with his ancestry, Elam Stoltzfus has crafted a new chapter in his life – a continuation of the narrative he once told through the lens of a camera filming alligators, black bears, and other creatures along the Apalachicola River. This time he is focused on the enduring legacy of family and history – the Nicholas Stoltzfus Homestead.

The Annual Auction

The Benefit Auction, held every first Saturday in May since 2003, is the primary fundraiser for the Homestead, supporting operating expenses, property improvements and educational programs.

Saturday, May 3 at 9 a.m.

1700 Tulpehocken Road, Wyomissing

What to Expect:

- Auction Items: Vintage books, household goods, garden supplies, furniture, quilts and more.

- Food: Homemade ice cream, soft pretzels, burgers, whoopie pies and other treats.

- Activities: Tours of the historic house led by Amish historian Sam Stoltzfus. A barn display featuring Masthof Publishers’ books, a featured author, Stoltzfus genealogy materials and local vendors.

For more information, visit nicholasstoltzfus.com.

Is this Elam the same as the quatlity home builder in

lancaster County?

No, it is not. Thanks for reading!