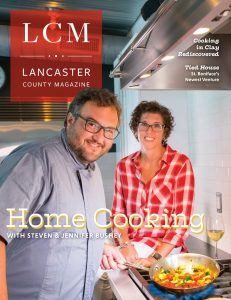

Steven and Jennifer Bushey have always taken comfort in being at home – even before the pandemic, they viewed home as their haven. “I instantly feel my blood pressure drop when I turn into the lane,” says Jennifer of the place they have called home for the last seven years.

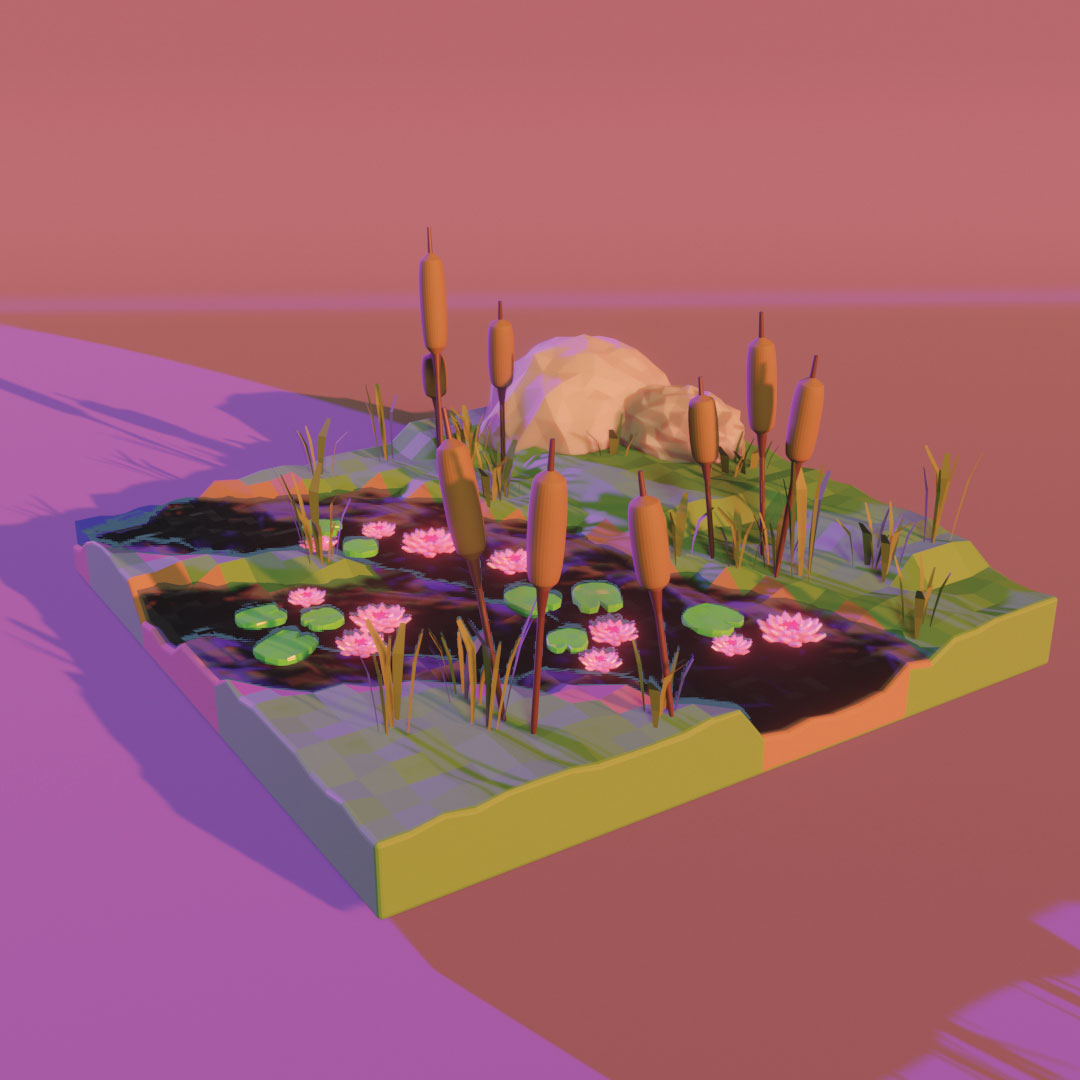

Once the kitchen was finished, Steven suggested they put the garage door to better use and build an outdoor-living area around it. The pool was the first post-kitchen project, followed by the sitting/dining area.

Jennifer’s blood pressure has no doubt skyrocketed over the past six months, as she and Steven are the owners of two food-related businesses – Manheim Twin Kiss and Rettew’s Catering. They’ve also faced the challenge of remote learning, as they are the parents of three children.

The Busheys’ storyline begins in 1959, when Jennifer’s grandfather, Ned Rettew, became a partner in the Manheim Twin Kiss, which opened in 1952. Her father, Bruce, eventually joined the business, transforming it during the 70s from a seasonal spot for root beer and ice cream to a year-round restaurant that specializes in burgers, fried chicken, barbecue and chicken pot pie (Wednesdays only, October-March).

Catering entered the picture when, ahead of his fifth-year high school reunion, some classmates approached Bruce with the idea of having the Twin Kiss provide food for the event. Bruce agreed to the proposal and went to work designing a menu. The evening was a success, prompting Bruce to expand Twin Kiss’s services. By the early 90s, Rettew’s Catering had become an entity all its own.

The Busheys’ outdoor-living area features a massive stone wall that contains a fireplace and a pizza oven. Steven found the unique vintage canoe lighting fixture online. Modular seating and a large dining table that can be subdivided into tables for four (or less) provide for togetherness or social distancing. “We wanted this to be a haven for family and friends,” says Jennifer.

Jennifer became associated with the business at the age of 12, when she began helping in the restaurant. “As a kid, I always remember car rides to work on Saturdays with my dad,” she says of “washing mugs and trays and helping to clean the dining room. I couldn’t wait until I was old enough to make cones and sundaes!” At 16, she began helping on the catering side. She’s also connected to food on her mother Vicky’s side of the family – Jennifer’s grandparents, Lee and Kathryn Zinn, owned Zinn’s Diner in Adamstown.

When it came time to chart her own course, “I tried to do something else,” she says of exploring a career in medicine through a class that was offered to high school students. “I knew what working in the hospitality industry meant,” she says, alluding to the nights, weekends and hard work that it entails.

Recognizing that medicine was not in her future, Jennifer weighed her options. “I even considered the CIA [Culinary Institute of America],” she recalls. She ultimately set her sights on Penn State. “The options were endless,” she explains of determining a career path. Still, she stayed true to what came naturally and settled on becoming a Hotel, Restaurant, and Institutional Management major.

Her first job post-graduation was at the Hilton Short Hills in northern New Jersey. In her estimation, working for Hilton would provide her with opportunities to branch out in a myriad of directions. One day, while shadowing one of the property’s managers, they cut through the kitchen, where Jennifer took notice of one of the chefs. She later learned his name was Steven Bushey and that he had just graduated from the CIA.

Her first job post-graduation was at the Hilton Short Hills in northern New Jersey. In her estimation, working for Hilton would provide her with opportunities to branch out in a myriad of directions. One day, while shadowing one of the property’s managers, they cut through the kitchen, where Jennifer took notice of one of the chefs. She later learned his name was Steven Bushey and that he had just graduated from the CIA.

A few days later, Jennifer’s roommate shared she had a date with a staff member. While her roommate was getting ready, Jennifer responded to a knock on the door, only to find Steven standing there. Fortunately for Jennifer, her roommate decided being friends would be the extent of their relationship. Thanks to the tight-knit staff “hanging out as a group,” Jennifer and Steven began spending time together. They were married on January 4, 2002.

Coming Home

A year before she married Steven, Jennifer moved back to Lancaster in order to become the general manager of Rettew’s Catering. In 2004, she became her father’s business partner. “We were partners for eight years,” she notes.

Steven, who grew up in Califon, New Jersey, made the move to Lancaster, as well. He instantly felt at home. “The two areas are very similar,” he says of the farming traditions and rural scenery they share.

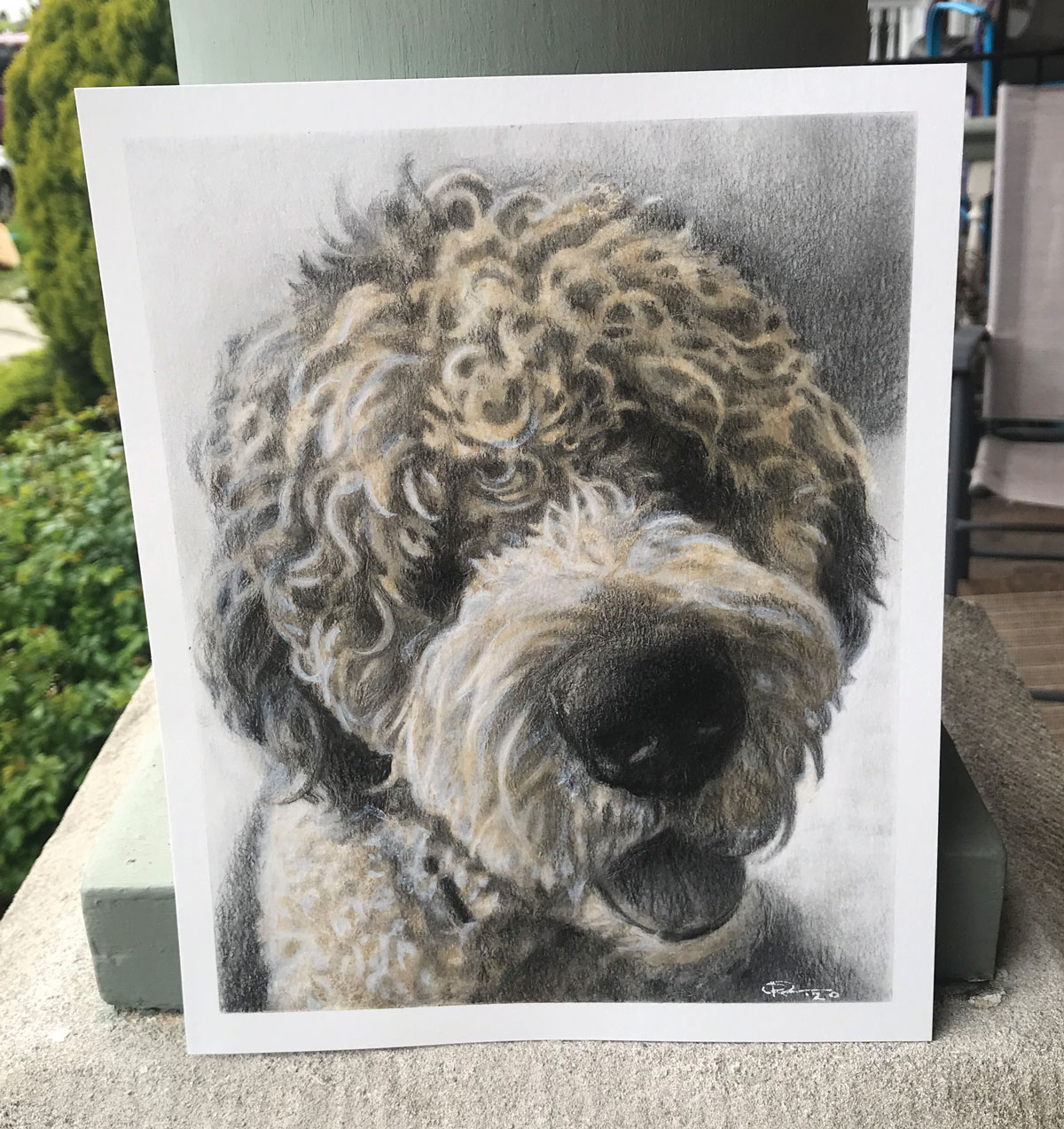

The kitchen addition is a complete departure from the traditional cherry kitchen that was original to the house. Steven’s urban/industrial design features a massive waterfall island (topped with soapstone), baked-on acrylic cabinetry, an appliance garage, a corrugated-steel ceiling, stainless appliances, industrial-look lighting, a subway tile backsplash that extends to the ceiling and a glass garage door.

They decided Steven would go in his own direction. “I didn’t know if I could handle working with both my father and husband,” Jennifer admits. “Besides, we had a very loyal chef on staff who had been with us for years.” So, Steven pitched in on an as-needed basis.

As much as he loves to cook, Steven possesses another talent – remodeling and construction work. He launched SB Construction, which essentially started as a handyman service and morphed into a full-scale construction company that specialized in restaurants. FENZ was one such project in which he was involved.

While he would have loved to include folding patio doors in his design, Steven found the cost to be beyond his budget. The roll-up glass garage door serves the same purpose – connecting the kitchen to the outdoor-living area.

Following the Great Recession, changes began to occur at Rettew’s. Bruce announced his retirement from the catering business in 2011. “We had a great run as partners but I couldn’t help but wonder if he would really be able to stay away – especially since he kept an office on property!” she explains of his continuing involvement in the restaurant. (He fully retired in 2018.) Then, Rettew’s long-time executive chef announced he would be leaving. It was time for Jennifer to find both a new business partner and a new chef. Steven answered the call.

The simple lines of the kitchen didn’t mesh with overhead cabinets. Instead, Steven provided space for a large restaurant-style pantry that is accessible to both the kitchen and dining room.

Building a Home

In 2012, the Busheys began searching for a new home. Subsequently, some friends also decided to look for a new home, deeming their current home – circa 1980s – was in need of some ambitious remodeling they didn’t care to undertake. Steven and Jennifer had always liked the wooded acreage and with his construction skills, remodeling the house would not be a problem. So, they bought their friends’ property. “The house wasn’t really our style,” he says of its colonial vibe. “But, I knew I could make it our own. I really wanted to get away from the formality of it. I like simplicity in design.”

Steven was especially anxious to design a new kitchen. He envisioned replacing the traditional design with a more urban/industrial look. Not liking the space constraints of the original kitchen, he proposed they build an addition to hold the kitchen and pantry. (The original kitchen became the dining room.)

Five years ago, he began the process by taking down walls – in order to create an open-concept kitchen/dining/family room area – and building the addition. His plan for the kitchen called for a huge island topped with soapstone. “I looked at and touched soapstone for months,” he recalls. Overhead, the ceiling would be lined with corrugated steel.

With the exception of one overhead cabinet, the sleek baked-on-acrylic cabinetry would be relegated to pull-out drawers. “Our moms didn’t understand the lack of upper cabinets,” Jennifer recalls.

Steven solved the storage issue by designing a huge pantry that mimics one you would find in a restaurant (complete with two swinging restaurant-style doors). An appliance garage in the kitchen holds items such as a coffee maker, a toaster and other items that are in use on a daily basis. As for the storage-friendly pull-out drawers, Steven was looking ahead – they are easily accessible to kids who are assigned chores such as setting the dinner table or emptying the dishwasher.

The island multitasks, as it supplies plenty of storage via cabinets and drawers, holds appliances, provides prep space and functions as a buffet. The island is also lined with seating, making it a magnet for guests. “Everyone always ends up in the kitchen!” Jennifer reports.

For the floor, he proposed concrete embellished with flecks of glass and slivers of mirror and finished with epoxy. “It’s really durable,” he points out.

Steven also envisioned merging indoor and outdoor spaces. He researched the folding patio doors that he began to see on home shows but found them to be cost-prohibitive. Then, the idea occurred to him of using a glass garage door. “People didn’t get what I wanted to do,” he recalls. Jennifer remembers a visitor asking if the kitchen had once been their garage. Steven rebuffed the dubious questions and comments. “I got the look I wanted at about a fifth of the cost,” he says.

The final touch was the stainless appliances. “I love my stove,” he says of the Wolf model he selected.

The pull-out drawers make setting the table or unloading the dishwasher easy for both adults and kids who are charged with such chores. Their accessibility also helps to reduce accidents – no more shattered dishes/glassware to clean up.

The kitchen addition prompted more ideas. “We decided that because of our schedules, we would really gear our home to family and friends,” Jennifer explains. “We wanted our home to be a haven everyone could enjoy. We’re not out-on-the-town kind of people. We don’t travel. We like to be home.”

Steven proposed they put the garage door to optimal use and utilize it as a portal that would connect the kitchen to an outdoor-living area. The first project was the swimming pool. “It’s nice,” says Jennifer. “We can be working in the kitchen and be able to keep an eye on the kids when they’re in the pool.” The pool was joined by a dining/sitting area that includes a massive stone wall that holds a fireplace and pizza oven. The most recent project saw the addition of a roof over the area.

In the age of coronavirus, the dining tables and modular furniture can be configured to allow for togetherness or social distancing.

The Family That Cooks Together …

Like most families, the Busheys have been cooking up a storm during the pandemic. “Covid has not been very good for my waistline,” Steven jokes. Eve, who is in 5th grade, appears to have the makings of a future chef. She loves to experiment. Her favorite “job” at Rettew’s is helping pastry chef Danielle Lillich. Assisting her dad at the pizza station, she was well versed on herbs, oils and cheeses. She’s also taken an interest in the chickens that now live on the property.

Steven learned the art of making pizza from the pros – as a teen, he would “work” in pizza shops during trips he made to Italy with his grandparents.

While Gus, who is in 8th grade, likes to cook, his strength appears to be in the area of logistics and management – he enjoys assembling all the items that will be needed for an event. As for Sal, he may have a future as a food critic. What 7th grader can describe the taste sensations of sea bass? Sal can!

All the while Steven was making pizza, the kids were sourcing the pantry for the ingredients to make a dessert pizza that appeared to be inspired by s’mores. The three did a taste-testing and decided “something” was missing. Their father offered a few suggestions to improve their creation. ‘All three of them have good palates,” Jennifer notes.

The Busheys have also jumped on another Covid trend – RVing. They discovered the joys of RVing several years ago and began renting rigs. This year, they decided to take the plunge and buy a travel trailer. “We bought it just before the pandemic,” Steven notes. While Gus dreams of heading for Utah, the family has been taking short trips to destinations such as the Poconos. “It’s perfect,” says Jennifer. “We can take off for a few days during the week and be back in time to get ready for a weekend event.”

Catering to a Pandemic

Gut-wrenching might best describe the feelings and emotions the Busheys have experienced over the last six months. According to Jennifer, between mid-March and mid-July, 50 of Rettew’s contracted events were either canceled or postponed. Weddings that had been scheduled over that time period were either drastically scaled back or have been put on hold. “We’re now at the point where weddings are being postponed for a second time,” she says.

Of course, the cancellations and postponements have a trickle-down effect and impact floral designers, linen providers, musicians, rental companies and the list goes on. Because 70% of Rettew’s wedding clientele are from outside the area, the local economy – hotels, restaurants, shopping venues, tourism – is further affected. The industry is a tight-knit one and its members have been leaning on one another for support during the pandemic. “I am on the phone with venue owners and colleagues on a very regular basis,” Jennifer explains. “We can truly feel each other’s pain right now.”

Jennifer became a member of a Pennsylvania Restaurant & Lodging Association task force that was formed to provide suggested guidance on events to Governor Wolf’s team. “The PRLA has been doing an amazing job of keeping members updated on the changing situation,” she says.

After years of renting RVs, the Busheys decided to invest in their own travel trailer earlier this year. In July, they spent a week in the Poconos and in August, they spent a long weekend at Watkins Glen in New York.

“We’ve gotten through bad times in the past, and we’ll get through this,” Jennifer says of both her business and those of her neighbors in Manheim. “The other day, I was talking to the owner of a neighboring business and I asked him which was worse, the flooding in 2011 or this. He said it’s the pandemic. At least with the flooding, you knew it would come to an end. With the pandemic, you just keep taking hit after hit.”

Indeed, panic ensued across the state on July 15, when Governor Wolf announced that in-house capacity at restaurants and event venues would be cut to 25%. “Just when we thought things were beginning to turn around and we were ramping up for the fall, that came down,” Jennifer relates. “It was a gut punch.”

Steven, ever the optimist, has adopted “gotta think positive” as his mantra. So, they carry on. Their first wedding was scheduled for late July. They were also determined to host their first “food tasting” in months. The tastings that are hosted by Rettew’s Catering are primarily aimed at couples getting married and are events in themselves. “We hold them at venues in our backyard such as The Booking House and Supply and show the guests what we can do,” says Jennifer of signature cocktails, food stations, desserts and hors d’ oeuvres such as Steven’s popular mini-tacos that make guests feel as if they are at a reception. “Because we’re at a venue there’s nice energy,” she explains. “People come away with totally new ideas for food and desserts. Customization is our specialty.”

Going forward, she is convinced potential clients will be paying attention to other aspects of food service. “The pressure is on for caterers to demonstrate how food service can done in a safe way,” she says. Self-service buffets will undoubtedly fall victim to the coronavirus. Jennifer expects that table-side service will become the new standard.

The Twin Kiss – whose manager, Mark Murr, has been with the company since 1987 – has proven to be a lifesaver. “We’ve been hands-on at the restaurant since the beginning of the pandemic,” Jennifer notes. “We were able to quickly adapt to take-out – before the pandemic, 35% of our business was take-out.” It was also a stroke of luck that the Busheys installed a drive-up window at the restaurant in 2019. Recognizing that take-out would be their salvation, they ramped-up service by offering online ordering. “An app is the next step,” Jennifer remarks.

“I kind of wish I still had my food truck,” Steven says of a past venture. “That was before kids,” Jennifer explains. “We have enough on our plates! But, it was fun.”

For more information, visit rettewscatering.com.