Tis the season to indulge in holiday spirits! This month I set out to discover what makes a quality cocktail with local flavor. In doing so, I stumbled upon a Pennsylvania history I never imagined: a heritage of distilleries in Lancaster County that transcends even that of modern-day Kentucky.

Whether or not you’re a whiskey drinker, it’s difficult to imagine Lancaster’s countryside filled with rye fields and dotted with distilleries. Such a scenario existed during the 18th and early 19th centuries. According to an article read before the Lancaster County Historical Society in the 1920s, 183 distilleries had existed in Lancaster County in 1813. Twenty-seven years later, just ahead of the temperance movement and the Civil War, the county total fell to 102 distilleries (along with 135 grist mills and eight breweries).

Distilling operations could also be found throughout the region. One of the most notable took root in neighboring Lebanon County (Schaefferstown), where John and Michael Shenk started producing pot still whiskey in 1753.

It begs the question: What would Pennsylvania’s economy and agricultural industry look like today had Prohibition never existed?

A Perfect Recipe

What was the reason behind the proliferation of distilleries? A need grew out an abundance of rye grain harvested across the region’s farmlands. A surplus of rye could fall plague to ergot mold, a hallucinogenic, which some theorize spurred on the Salem Witch Trials. Rather than let crops go to waste, farmers could preserve their rye yield and turn it into a tradable commodity, a currency by the gallon or barrel.

A bottle of Stoll & Wolfe’s first batch of Bomberger’s blended whiskey signed by Dick Stoll. Attempts to utilize the Bomberger’s name were justified but held up in court by a new, larger distillery in Kentucky that claimed the Michter’s name was abandoned, thus giving birth to the Stoll & Wolfe name.

Blending distilled whiskeys was another component to our local history, a tradition that continues today. Where bottled in bond is from one distiller’s single-season yield, blends are the opposite.

To go a step further, a wealth of rye coupled with water filtered by limestone and rich in dissolved dolomite (similar to the water content in Kentucky), paired well with German milling technology. While most of the world’s supply of bourbon comes from Kentucky, it is not a technical requirement for the whiskey to be distilled there. It has everything to do with defined “laws” as to how they’re made, including what portion of ingredients goes into whiskey such as rye, corn, barley, wheat and so on.

Rye whiskey, as you can imagine, must be 51% or more rye, producing a dry, spicy delight. Its sweeter cousin, bourbon whiskey, must be 51% or more corn-based, stored in new, charred oak barrels for added dimensional flavor and color, and bottled at a minimum of 80 proof.

Boehm Transitions to Beam

If I may interject a bit of foreshadowing before we temporarily depart from the subject of Kentucky, it’s of note that many early frontier-bound settlers traveled through Pennsylvania. Jacob Boehm was one of them, emigrating from Germany in 1740 to what is now Berks County, which was once a part of Lancaster County. The Boehm family owned land purchased from William Penn in Willow Street, where the Boehm Chapel stands to this day. The family name later changed to one you may find more familiar, “Beam,” which we see today on thousands of bourbon bottles from Kentucky.

In 1788, Jacob moved to Kentucky ahead of a legal revolution in the distilling community.

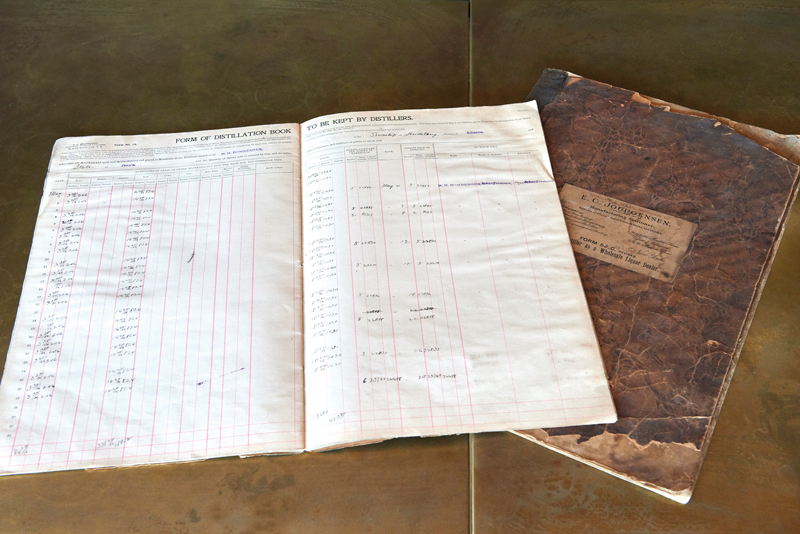

Original production ledgers from the Bomberger’s Distillery dating back to 1915, separately denoting the grains used in the mash bill and whiskey yields by the barrel.

Prohibition

When Prohibition took effect in 1920, the distilling industry in Pennsylvania died almost overnight. Farming rye was replaced by other crops such as tobacco. Whiskey could still be prescribed by a doctor as medication, so distilling in Kentucky continued legally on a limited basis.

Pennsylvania’s Old Overholt, founded in West Overton in 1810, was bought by National Distillers, located in Louisville, and the sale included a medicinal whiskey license. Sales of pint-sized bottles of “medication” helped to weather the storm until Repeal Day on December 5, 1933, with the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment. In that very same year, our own local distilling hero was also born …

STORY CONTINUED BELOW >>>>

Holiday Spirits

Spoonful cocktail made of rye whiskey or bourbon, apple cider, lemon juice and ancho chili-infused maple syrup. Stoll & Wolfe was honored for their rye whiskey, achieving 95 of a possible 100 points in tasting competition.

Now that you’re armed with the conversational history of Pennsylvania’s rich distilling past, here are a few simple tips to party up your cocktails before a flurry of guests arrives this winter.

Blends and Infusions

Adding herbs, spices and fruits to your spirits will instill new flavors into the essence of a drink. The additions could include berries, citrus, pineapple, vanilla, rosemary, peppers and basil, to name a few. Dried herbs and spices can be toasted on a skillet for added dimension. Candy can also be a popular choice; try Swedish fish, Hot Tamales or peppermint. For the best results, keep the combinations simple.

Add quality ingredients to a versatile liquor such as vodka, allowing it to steep for a few days, agitating regularly. You’ll have a simple yet custom and deliciously blended conversation piece.

Stock the Pantry

Cinnamon (ground or sticks), olives and Old Bay Seasoning are some of the many seasonings and trimmings your Christmas cocktail might require. Luxardo Maraschino Cherries, while expensive, last for quite some time and deliver quality flavor. Check your supply of fresh fruit and bitters for making the occasional Old Fashioned or Manhattan.

Freezer Burned Ice

Even ice cubes can become freezer burned, and that undesired bitter taste will infuse in your drink. If you know you’ll be mixing a large batch of cocktails, reset your ice cube supply a few days in advance. You can also chill your glasses with ice water ahead of pouring.

Don’t Muddle the Mint

Muddlers are a great way to puree fresh fruit, spices or herbs in a cocktail, but they have their bounds. Have you ever watched (or heard) bartenders smack mint in their palms when preparing drinks? Smacking the mint releases oils and flavor without breaking down the leaf, thus eliminating bits of leaf fiber floating throughout your drink.

Shaken, Not Stirred

There’s a time for shaking and a time for stirring. Shaking a cocktail changes the drink in a way that stirring cannot. As ice is added, the drink will chill faster – you can tell it’s ready when the metal shaker frosts over (usually after about 15 shakes). The ice will melt slightly, imparting water that often opens up the flavor. If you want to serve an undiluted drink, stirring is the way to go.

>>>

Dick Stoll

Dick Stoll was born just a month earlier in Lebanon County. Following his service in the Korean War, he became a construction worker. That spring, he received a serendipitous call from Kirk Foulke of Lancaster, regarding a new building in Schaefferstown.

What had started as the Shenk’s distilling operation in 1753 had changed hands many times over the years, finally taking up the famous Bomberger’s name. During Prohibition, Bomberger’s Distillery waited like a sleeping dragon to be awakened, and records from that period of time are difficult to confirm. The accounts vary by party, but Lou Forman came into ownership after Prohibition, and around 1949 he talked Foulke into buying it from him.

At the time Dick arrived on the job site, it was known as Kirk’s Pure Rye Distilling Company. Foulke wanted the waste grain for his cattle farm and had little interest in distilling. The distillery would soon be sold yet again to Pennco, owned by the giant, Continental, based in the Philadelphia area.

Dick was hired to work at the distillery, and in 1954 they started it up with around a dozen people working together, operating six days a week. Due to his years in the Navy, Dick had a mechanical background, so he was assigned to the barrel crew. When a spot on the maintenance crew opened up, he took it.

In 1955, Dick met Charles Everett Beam, who moved from Kentucky to Pennsylvania to work for Pennco. It was Beam who taught Dick about distilling. The two became friends and enjoyed hunting and fishing together. Beam had a heart attack in 1972, which prompted him to step down.

Lou Forman, who had repurchased the business with some partners, then asked Dick if he’d take over as master distiller, which he did. In Dick’s own words, he held “all the jobs in the plant at one time.” Four years later, Dick met his future wife Elaine, a school teacher who served as a tour guide at the distillery in the summer.

Michter’s Distillery

Forman and Beam created what they called Michter’s Original Sour Mash Whiskey. (Michter’s was a blend of the names of Forman’s sons, Michael and Peter.) It was a whiskey in a category of its own, fitting the grain bill of neither a rye nor bourbon whiskey. It was designed to stand out, primarily to pursue the market created by Maker’s Mark.

The business eventually took the name, Michter’s Distillery. According to Dick, as late as the 1970s and 1980s, people still expected rye to come from Pennsylvania, not from Kentucky. As is common in the industry, Michter’s distilled for a number of labels, including A.H. Hirsch, Sam Thompson Rye and Wild Turkey.

Last Call

Over time, the demand for wine and vodka took off, and whiskey sales dropped at the small distillery. It was again sold, and the owner, Ted Veru, legally funneled-off money before his disappearance ahead of bankruptcy in 1983. Commonwealth Bank took ownership, but the distillery never recovered.

On Valentine’s Day 1990, while serving as Michter’s master distiller, Dick was instructed by the bank to shut down operations. A sign was put on the door, “Closed until further notice.” That day never came.

The remnants of what remained in the Michter’s warehouses were distilled by the government into ethanol and racing fuel. It was also sold to settle debts. The stills were shipped off to Kentucky, and while an application was accepted for the site to become part of the National Registry of Historic Places (it also received National Landmark status), not much of the operation remains.

After more than 35 years at the distillery, Dick Stoll’s bottle had run dry.

Stoll Meets Wolfe

While we will never know what Lancaster’s economy and agriculture would have looked like in the absence of Prohibition, our distilling history has been given a new shot thanks to Erik and Avianna Wolfe, who set out to open a new distillery in 2011. Subsequently, a mutual friend and local Michter’s Whiskey historian, Ethan Smith, introduced them to Dick Stoll. According to Erik, “There would be no Stoll & Wolfe without Ethan Smith.”

Ethan recalls contacting Dick on a cold call 10 years ago, inquiring about Michter’s and meeting up with him at the old Michter’s site for the first time.

Knowing both Dick and Erik, he arranged a meeting of the two, and a partnership was born. Being the first person since Prohibition to operate both a pot and Coffey still, Dick’s wisdom has been foundational to the pair, a living legend in his own right.

It seems Dick’s wisdom might have something to do with genetics. Erik’s parents, Jim and Diane Wolfe, conducted extensive historical and genealogy research and made the remarkable discovery that Dick is related to the Beam family.

Were it not for the Smith, Stoll and Wolfe families, much of my findings presented here would have been lost to time. It is with much gratitude that I thank them all for sharing their knowledge with us.

Stoll & Wolfe Distillery, 35 N. Cedar Street, Lititz. Stollandwolfe.com.

SHARE

PRINT